Eugen Weber, France: Fin de Siècle -- The Notion of an End of the Century

End-of-century trips less lightly off the tongue than fin de siècle. This

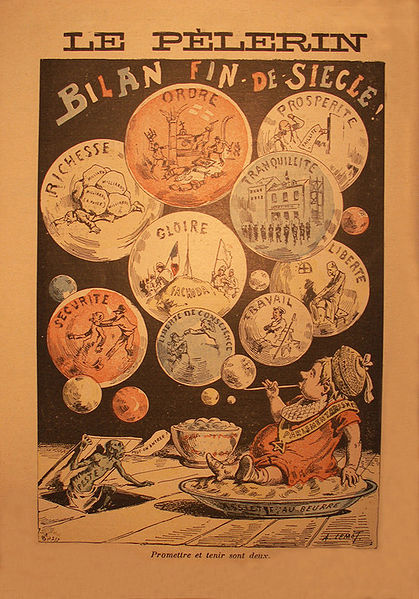

"Fin de siècle Balance Sheet To promise and to produce are two different things" |

may bewhy the term remains associated mainly with France, where it was coined while the nineteenth century still had a while to run. Just what it meant at first was not entirely clear. It could denote "modern" or "up to date." But novelty went with uncertainty and a certain insecurity, and eventually a certain decline of standards. A shoemaker could be praised for being a traditional cobbler rather than fin de siècle. Soon the negative connotations of the term drove all others out. When, in 1891, a judge described young lawyers as fin de siècle, the press found this too harsh, likely to evoke "legitimate protests."

That same year, a provincial newspaper's attack on the local prefecture as fin de siècle led to a duel and court action that ended in a fine for the defaming sheet. And when a Paris court judged a blackmailer who lived off his wife's prostitution, it was to hear him explain that he was no more than "a fin de siècle husband." The words were everywhere; they could be applied to anything and everything:

Fin de siècle! partout, partout

. . . il sert à désigner tout.Fin de siècle! Everywhere

. . . It stands for all that you might care

To name ...

Since art imitates life, when it does not inspire it, literature soon adopted the vision. In 1891 Joris Karl Huysmans (naturally) denounced "the ignoble spectacle of this fin de siècle." But more vulgar, hence more audible, voices intoned the same refrain. An 1888 play called Fin de siècle turns around shady deals, adultery, and murder; a dreary novel of the same title, published in 1889, tells of a rich young man whom boredom, gambling, and misplaced affections lead to suicide in 325 weary pages. As 1890 ended, a new financial weekly, Le Fin de siècle promised spicy revelations of financial scandals. It foundered with the year, bequeathing its title to a more "literary" review, suggestively illustrated to support its argument that vice is more interesting than virtue. Presumably more representative too: "whoever wants to please today has to be fin de siècle or cease to exist."10 What were the fin de siècle ideas of this resolutely fin de siècle journal?

"No more rank, titles, or race," explained the editor, François Mainguy, in the first issue. "All is mixed, confused, blurred, and reshuffled in a kaleidoscopic vision." The fin de siècle's character at its most acute was competition, "struggle for life," and, above all, striving to satisfy les appétits du ventre.

It would be even more the appetites of the lower stomach that Le Fin de Siècle set out to satisfy, competing with La Vie Parisienne and other more or less vaguely salacious publications that could afford to rent well-known authors (Emile Zola, Alphonse Daudet, Aurélien Scholl, Octave Mirbeau) at a good fee. In 1893, as a publicity stunt, Mainguy set out to imitate the art students' popular bal des Quatre-z-Arts,by organizing a bal fin de siècle. His scheme became a great success when the model he hired to represent Beauty was arrested and taken to court for wearing nothing beside (or beneath) a transparent black chemise, while an accompanying nymph was accused of dancing without even that to keep her warm. The outrage public àla pudeur brought the girls fifteen and eight days in jail respectively, while Mainguy was sentenced to one month. Circulation soared.

Moral anarchy, or what was so described, subverted ideas and standards hitherto taken for granted, at least in public. There were no more beliefs, vice was everywhere; it was not merely a fin de siècle, wrote Fin de siècle,but a fin de race: the tag end of an ailing race (people), "in which only one cult survives, that of love." Love of course meant sex, though not procreation. No wonder that growing numbers, especially within the Catholic Church, believed they saw the Devil's hand behind the accelerating decay. In 1891 the Abbé Jeanin had published Eglise et fin de siècle, which decried the decadence of the times. By the end of the century, the end of the world seemed nigh. The World's End Soon,Arthur Lautrec promised in 1901; in 1904 Jean Rocroy's more precise The End of the World in 1921 (As Proved by History) was printing its 20,000th copy.14

One did not have to go so far to appreciate the interest of a time of accelerated change, a society that seemed about to alter in essence as it had in appearance--"a society about to disappear," already agitated and alarmed "by a thousand important symptoms of degeneration."15

The notion of end, somehow, goes with thoughts of diminution and decay. A hundred years earlier, Sébastien Mercier, dealing with a less hangdog century's demise, had also found misery, gloom, and anxiety predominant; he concluded that it was almost impossible to be happy in Paris. Things had become worse since then: defeat and occupation in 1814-15, defeat and occupation again after 1870, suggested, then confirmed, that France's conquering days were drawing to a close, to be replaced by the new, uneasy experience of decline.

Decadence, sketched by Romantic poets, would be asserted by Naturalist description, hailed by those who savored its concomitant refinements, denounced with bitter satisfaction by those who saw their world unraveling. At midcentury, feelings of this sort appeared to be confirmed by medical research, when Dr. Benedict Morel published his Treatise of the Physical, Intellectual, and Moral Degenerations of the Human Race and of the Causes That Produce These Maladive Varieties (1857). The debate was joined around Morel's thesis. "For the last quarter-century," a medical man complained in 1876, all one hears is "We are degenerate! We are in decadence!" As if to confirm this, statisticians tell us that the population is falling, the average height of recruits diminishes, the number of draft rejects grows, morality wanes, crime flourishes, mind and body tend to deformity, cretinism, idiocy, lunacy, and so on. Some of these assertions were demonstrably false, others disputable. Statistics varied, as they always do. But the best that opponents of the Decadence thesis could produce was not a refutation, but arguments that the "pretended physical degeneration" of the French was relatively unimportant when compared to that of other Europeans.16

The issue was not one that a scientific approach could settle. The evidence, it seemed, lay all around. Among those who discussed such things, or listened to the discussion, the debasement and decrepitude of the society and of its values seemed beyond argument. The more so when it hit close to home: troubled sleep, troubled digestions, bad circulation, fatigue, and so on. Dr. de Fleury, describing The Major Symptoms of Neurasthenia (1901), could only deplore "this discouraged lassitude, this intellectual and physical impotence," that characterized it. Within a decade things had got worse. Neurasthenia, Dr. Grellety asserted, was the maladie du siècle. "Neurosis lies in wait for us and weighs more heavily all the time . . . Never has the monster made more victims, either because ancestral defects accumulate, or because the stimulants of our civilization, deadly for the majority, precipitate us into an idle and frightened debilitation." As Pasteur Vallery-Radot remembers, "it was fashionable in 1910 to delight in melancholy."17

This may explain why a contemporary publicist, reviewing the professions a bright young man might choose, focused on medicine, where "he would find a flourishing career by dint of the anxieties, the neuroses, and the general disorders that reign among the higher social classes."18

The higher social classes, or at least their sensitive offspring, knew that tender nerves were evidence of refined sensibilities. Baudelaire had admired the nervousness of Edgar Allan Poe's writing and the nervous intensity of Wagner's music. Baudelaire's admirers venerated the poet's "glorious nervous complaint that would affect all sensitive souls after him"; they sought, like him, to "exasperate their ailment." Félicien Rops, the great etcher, claimed to work with his nerves. Maurice Rollinat's poems Les Névroses date from 1883. For Zola, the work of the Goncourt brothers was "a sort of vast neurosis"; and Taine "fits well in our society of nerves." Edmond de Goncourt considered Degas a neurotic. Huysmans' Art Modeme (1883) described Berthe Morisot as a nervous colorist, Guillemet as "a packet of nerves under control," and Gauguin as "a skin beneath which the nerves vibrate," while Mary Cassatt offers "a whirl of feminine nerves transposed into her paintings."19

This stress on nerves and search for sources of nervous energy went hand in hand with a sense of enervation, loss of enthusiasm, lassitude, énervement d'esprit, a general degradation of energy apparently confirmed by the theory of entropy, derived from the second law of thermodynamics. But not only energy seeped away. Health and strength did so too, witness France's miserable performance in the demographic stakes. From the 1880s to the First World War countless voices rose to warn that the country was in danger of disappearing. And, as its numbers shrank, those who were left rotted from the inside.

The hold of the Church had weakened, but the wages of sin, to be paid not in the next world but in this, were no less terrible for guilty and innocent alike. Oppressed, exploited, the people struck back through its womenfolk who transmitted syphilis to bourgeois males. Picked up in the street, the brothel, or the maid's room, their corruption would necessarily affect the "race." The belief that vice carries its own punishment through venereal disease that rots its carrier and his descendants joined with vulgarized Darwinism to suggest that, like families, societies and social groups were subject to degeneration. "The degeneration of the race," Andre Derain wrote to his friend Vlaminck, "pours out of our every pore . . . We are the mushrooms of ancient dunghills."20

In the French version offered by Antoine's avant-garde theater, Ibsen's Ghosts spoke no longer about the hereditary effects of syphilis but those of alcoholism.21 But the vice or alcohol that sapped the ruling classes, depraved and brutalized the lower. If the race ran to seed, the result was further corruption: physical degeneration made for crime; digénéréscence and criminalitéwere linked in title after title, as in Zola's saga of the Rougon-Macquart clan. And before long a logical conclusion was drawn: modern man was going against the principle of the survival of the fittest. Some of the very institutions that an advanced society creates cause the decline of the race. Modern man looks after the weak, the backward, the degenerate. Public assistance, asylums, clinics, and hospitals keep people alive--idiots, imbeciles--to breed other degenerates whose survival contributes to the social disaster. Such counterselection should cease: criminals, degenerates, and mental defectives should be sterilized--freely or, if need be, "by fraternal pressure." Else, how can society be preserved?22